Chapter 1 Thinking About Numbers

1.1 Introduction

This chapter highlights why statistics is so relevant and important in society.

1.2 Why use statistics?

The term ‘statistics’ can have a wide range of meaning and usage. Below are some thoughts of others.

Statistics is the science of collecting, organizing, and interpreting numerical facts,which we call data.

Moore & McCabe(1993)

The subject matter of statistics is the process of finding out more about the real world by collecting and then making sense of data.

Wild & Seber (1999)

Statistics is away of reasoning, along with a collection of tools and methods,designed to help us understand the world.

Richard Veaux (2006)

I keep saying the sexy job in the next ten years will be statisticians. People think I’m joking, but who would’ve guessed that computer engineers would’ve been the sexy job of the 1990s?

Hal Varian, Chief Economist at Google (Anonymous 2009b)

More cynically:

In earlier times, they had no statistics, and so they had to fall back on lies.

Apocryphally attributed to Steven Leacock, Economist

Scientists use numbers for a variety of reasons. Numbers are a universal, precise language that can be understood by all. Consider the distinction between “I saw some whales” and “I saw 21 whales”; the quantity “some” is open to interpretation whereas “21” is precise. Numbers can express amounts (e.g. “30 bushels of corn”), express centrality (e.g. “the average male Briton is 176 cm tall”) and express variation (“the minimum score was 10 and the maximum was 100”). By using probability (see Chapter 4), we can express uncertainty (e.g. “there is a 50% chance that it is going to rain”).

We can distinguish pattern, or signal, from random noise and classify things. Using numbers can aid objectivity; qualitative judgements may be more open to bias. That isn’t to say that quantitative judgements cannot be biased, but it can be easier to identify any biases.

Putting all these things together, ultimately we can use numbers to test, or assign a relative value, to different hypotheses.

Statistics distinguishes itself within the mathematical sciences by its focus (or even obsession) with randomness - it is the inherent unpredictability of many real-world problems that forces us to quantify our uncertainty and express our answers probabilistically. This frank admission of uncertainty is what makes the statistical treatment of problems honest, yet it is arguably responsible for the poor press that statistics and statisticians often receive. However, the admission of uncertainty in an answer is far preferable to expressing incorrect answers with great certainty - it is rare to be able to draw certainties from the analysis of real data. Better to be roughly right than exactly wrong (Fingland 2011).

1.3 Why model?

Model - A simplified or idealized description or conception of a particular system, situation, or process, often in mathematical terms, that is put forward as a basis for theoretical or empirical understanding, or for calculations, predictions, etc.; a conceptual or mental representation of something.

Oxford English Dictionary (1989)

Essentially all models are wrong, but some models are useful

G.E.P. Box (1976)

The quote by G.E.P. Box is particularly apposite; the purpose of a model is typically for explanation and prediction. Explanation can come from building and using the model; prediction only from using the model. In a statistical context, they are mathematical abstractions of a reality where the variation in the system is simplified and characterised as a distribution (see Chapters 5 and 6).

Models are often mechanistic, i.e. the model explains the processes that occur in the system of interest. Meteorologists might create a model of atmospheric processes in order to predict the weather. It may contain terms for pressure, temperature and proportions of different gases in the atmosphere. However, not all models need to be mechanistic. A pragmatic statistician might create a model to try and answer the question “If it rained today, what is the probability it will rain tomorrow?” such a model does not explain the weather but it might adequately predict the weather.

1.4 Examples of statistical claims

There are lots of numerical claims about the real world; a few are listed below. How reliable are the claims?

1.4.1 Coffee ‘may reverse Alzheimer’s’

“Drinking five cups of coffee a day could reverse memory problems seen in Alzheimer’s disease, US scientists say. The 55 mice used in the University of South Florida study had been bred to develop symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. When the mice were tested again after two months, those who were given the caffeine performed much better on tests measuring their memory and thinking skills and performed as well as mice of the same age without dementia.”

BBC 5th July (2009a)

Q1.1 Should we rely on this claim?

Q1.2 Can we generalise our results from 55 mice to humans?

1.4.2 Abundance of prized sturgeon

“Experts can’t agree how many beluga sturgeon are left in the sea. At stake is the future of one of the world’s most sought-after fish and its coveted black gold.”

New Scientist, 20 Sept. (2003)

CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) said there were 11.6 million beluga sturgeon in 2002; the Wildlife Conservation Society says maybe less than 0.5 million.

Q1.3 Why would estimates from different sources vary so much?

Q1.4 How would you approach such a problem?

Q1.5 What if you had very limited resources to try and answer such a problem?

1.4.3 Extrapolating sprinting speed

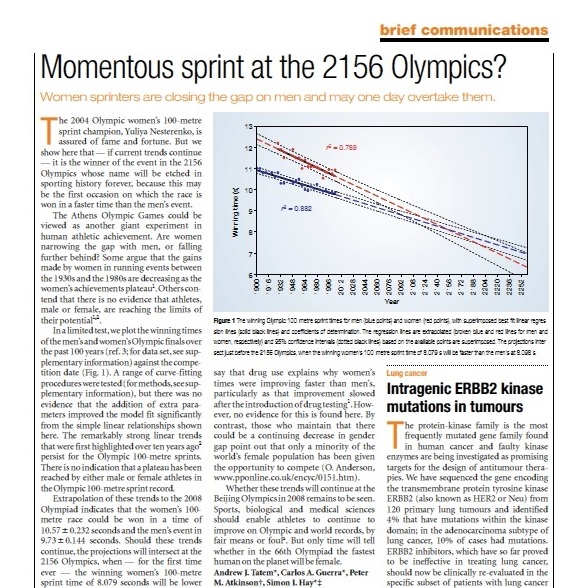

A brief article in Nature (Tatem et al. 2004) stated that “Women sprinters are closing the gap on men and may one day overtake them” (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: A paper from Nature

Q1.6 Does this seem reasonable to you? Why?

Q1.7 What is the population they are generalising to?

1.4.4 MMR innoculation and autism

If a young child receives the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccination, are they more likely to become autistic than a child that did not receive the vaccination? In a 1998 paper in the Lancet, Andrew Wakefield and co-authors suggested that the MMR vaccination led to intestinal abnormalities, resulting in impaired intestinal function and developmental, 24 hours upto a few weeks of vaccination. This hypothesis was based on 12 children (Wakefield et al. 1998). This led to a considerable drop in the percentage of infants and young children being vaccinated.

Some problems identified with this work were:

too small a sample, not a random nor representative sample (the children had been referred to specialists),

there was no control group of healthy children for comparison (to see what percentage had autism)

4 of the 12 children had signs of autism prior to the vaccination

the authors inferred from this sample that children getting the MMR vaccination were more likely to become autistic than those not getting the vaccine. Thus generalising to all children who have had, or will have, the MMR vaccination.

Subsequently, in 2004, 10 of the 13 authors of the study retracted the paper, stating that the data were insufficient to establish a causal link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Arguably the paper lowered vaccination rates in the UK.

Q1.8 How safe do you think it was to generalise to all children who have had, or will have, the MMR vaccination?

1.4.5 Two SID deaths in same family

How likely is it for two children in the same family to die from Sudden Infant Death (SID), or syndrome (cot death)? Mrs. Sally Clark was imprisoned in 1999 for the murder of her two infant sons. She was found guilty partially on the basis of Professor Sir Roy Meadow’s testimony who said that such an event, two SID deaths in the same family, should only occur with probability one in 73 million. Professor Sir David Cox, a former Professor of Statistics at Imperial College, London, told the General Medical Council’s fitness to practise hearing that the odds of two children from the same family dying from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) were much higher because they shared the same genetics and were exposed to similar environmental factors. He said Prof. Meadow’s testimony that the chances of Mrs Clark’s two babies dying of SIDS were “one in 73 million should be regarded” as an error (Anonymous 2005).

The use of statistics in court in the UK has recently been subject to considerable scrutiny see The Inns of Court Council of Advocacy and Royal Statistical Society (2017).

1.5 Summary

Numbers and statistics potentially gives us a very powerful way of interpreting and reaching conclusions about the world but they should be used carefully with consideration of bias and uncertainty. This course will help you to critically consider numeric data supplied in news articles and the different types of statistics that are reported.

1.6 Answers

Q1.1 We should be cautious relying on this claim, see next answer.

Q1.2 Consider this as a two stage problem. Can we generalise from 55 mice to all mice (of the species Mus muscularis)? Perhaps we can, but the laboratory strain of mice might be different to wild mice. Extrapolating to humans may be possible if the physiology of coffee metabolism is similar across species - but it might not be. Dogs, for example, metabolise theobromine, a toxic component of chocolate, at a far slower rate than humans. As a result chocolate is toxic for dogs but is not for humans.

Q1.3 Presumably CITES and the Wildlife Conservation Society are using different methods to estimate the sturgeon population. One or both may be wrong.

Q1.4 There could be a variety of ways to tackle a problem like this. The fish population could be estimated by seeing how many are captured by fishermen over a given area of ocean. Alternatively perhaps fishes could be marked and released and then recaptured which would allow an estimate of the population size.

Q1.5 Requiring fishermen to report their catch accurately might be the cheapest method, otherwise, a dedicated mark recapture approach as in the question above might be necessary.

Q1.6 It is a massive extrapolation into the future which assumes a linear trend. There must be a limit to the improvement in sprinter speed. A sprint could not be undertaken in zero seconds!

Q1.7 The “population” here is not men or women but sprint speeds of men and women.

Q1.8 Given it was a biased sample it was probably very unsafe to generalise to all children.