Chapter 5 Discrete random variables

[Professor Moriarty] is a man of good birth and excellent education, endowed by nature with a phenomenal mathematical faculty. At the age of twenty-one, he wrote a treatise upon the binomial theorem, which has had a European vogue. On the strength of it he won the mathematical chair at one of our smaller universities, and had, to all appearances, a most brilliant career before him.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1894)

5.1 Introduction

A random variable is a quantity that can take a range of values that cannot be predicted with certainty but only described probabilistically (Borowski and Borwein (1989)). The values can either be discrete or continuous. In this unit, discrete random values are considered; continuous random values are considered in the following chapter.

In this unit, we define:

discrete random variables,

probability mass functions,

cumulative distribution functions

expected values and expected variation of discrete random variables,

and three specific and useful random variables, Bernoulli, binomial and Poisson random variables.

Note that this chapter contains a lot of notation and many equations; please refer to the notation guide.

5.2 Discrete random variables

A discrete random variable is random variable which can only take a countable number of values.

As an example, consider tossing a fair coin twice; the possible outcomes are head-head, head-tail, tail-head and tail-tail. Assume that the variable of interest is the number of heads (denoted by \(Y\)) and so the resulting values, or sample space, for \(Y\) are either 0, 1 or 2 heads (Table 5.1).

| Outcome | HH | HT | TH | TT |

| Y | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

The variable \(Y\) is a discrete random variable; the outcome can only be a discrete value and we cannot predict the outcome with certainty but we can describe the outcome probabilistically.

5.2.1 Probability mass function

The probability mass function (PMF) is simply a mathematical description of the probabilities of outcomes in the sample space. We can construct the PMF for \(Y\), the number of heads when tossing a coin twice by considering the possible outcomes (Table 5.1). The sample space is either no heads, one head or two heads (i.e. \(S\)={0, 1, 2}). The probability of two heads, written \(Pr(Y=2)\), will be 1 out of 4 possible outcomes, thus \(Pr(Y=2)=0.25\). Similar calculations can be used to obtain the probability of no heads and one head (Table 5.2).

| y | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Pr(Y=y) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

The PMF tells us everything about the random variable \(Y\). It also has a special property in that if we sum \(Pr(Y=y)\) over all possible values in the sample space, we get 1.

If the sample space of a random variable denoted by \(X\) can be written as {\({k, k+1, ... , n}\)} then

\[\begin{align} \sum_{x=k}^{n} Pr(X=x) = Pr(X=k) + Pr(X=k+1) + ... + Pr(X=n) = 1 \end{align}\]

This property is easy to verify for the PMF of \(Y\), the number of heads:

\[\sum_{y=0}^{2} Pr(Y=y) = Pr(Y=0) + Pr(Y=1) + Pr(Y=2) = 0.25 + 0.5 + 0.25 = 1\]

Q5.1 Let event \(Y\) be the sum of the numbers resulting from throwing two fair, six-sided die. Calculate the probability mass function of \(Y\).

5.2.2 Cumulative distribution function

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) is derived from the PMF. For a discrete random variable called \(X\), the CDF provides the probability that \(Pr(X \le x)\). Thus, for the coin tossing example, the probability that \(Y\) is less than or equal to one head (i.e. \(Pr(Y \le 1)\)) is given by:

\[Pr(Y \le 1) = Pr(Y=0) + Pr(Y=1) = 0.25 + 0.5 = 0.75\] A similar calculation can be performed for all values in the sample space (Table 5.3).

| y | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Pr(Y=y) | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| Pr(Y<=y) | 0.25 | 0.75 | 1 |

The CDF is a useful tool in calculating probabilities over intervals of a discrete random variable. However, care must be taken in considering the endpoints of the intervals - are they inclusive or exclusive; this will be clearer with a more complicated example.

Consider the toss of a fair, six-sided die and denote it by \(X\); there are six possible outcomes (i.e. 1 to 6), all with equal probability (Table 5.4). We can obtain the probability that \(X\) is less than 5 from the CDF as follows:

\[Pr(X < 5) = Pr(X \le 4) = 0.6667\]

| x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Pr(X=x) | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | 0.1667 | 0.1667 |

| Pr(X<=x) | 0.1667 | 0.3333 | 0.5 | 0.6667 | 0.8333 | 1 |

What happens if we want \(Pr(X>x)\) or \(Pr(X \ge x)\)? These can be found using the complement rule (Chapter 4):

\[Pr(X>x) = 1-Pr(X \leq x)\] \[Pr(X\ge x) = 1-Pr(X < x) = 1 - Pr(X \le (x-1))\] Hence, the probability that \(X > 4\) can be found from \[Pr(X > 4) = 1 - Pr(X \le 4) = 1 - 0.6667 = 0.333\]

\[Pr(X \ge 4) = 1 - Pr(X < 4) = 1 - Pr(X \le 3) = 1 - 0.5 = 0.5\]

With discrete random variables, it is important to be careful with \(<\), \(\le\), \(>\) and \(\ge\) signs.

Q5.2 Using the PMF obtained for event \(Y\) defined in Q5.1,

a. Calculate the cumulative distribution function of \(Y\).

b. What is the probability that \(Y\) will be less than 7?

c. What is the probability that \(Y\) will be an odd number?

d. Include question to calculate an interval estimate.

5.2.3 Expectation

Although the outcome of a process is uncertain, the PMF can be used to determine what value might be expected on average, if the process was to be repeated many times. For a discrete random variable \(X\), with a finite number of outcomes \(k\), the expected value of \(X\), denoted by \(E(X)\) is given by

\[\begin{equation} E(X) = \sum_{x=k}^n xPr(X=x) \label{discexpx} \end{equation}\]

This is actually a weighted average where the probabilities are the weights (since the probabilities sum to one).

Using this equation, the expected value from tossing a die is therefore given by

\[E(X) = (1 \times 0.1667) + (2 \times 0.1667) + (3 \times 0.1667) + (4 \times 0.1667) + (5 \times 0.1667) + (6 \times 0.1667) = 3.5\]

The same calculation can be seen in Table 5.5.

| x | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Total |

| Pr(X=x) | 0.16667 | 0.16667 | 0.16667 | 0.16667 | 0.16667 | 0.16667 | 1 |

| xPr(X=x) | 0.16667 | 0.33333 | 0.50000 | 0.66667 | 0.83333 | 1.00000 | 3.5 |

The expected value from tossing a six-sided die is 3.5, i.e. \(E(X)=3.5\). We could verify this empirically if we were to throw the die a large number of times and compute the average value of all the observed outcomes. As the number of throws increases, the average will converge to 3.5 - the simple arithmetic mean of all outcomes. Hence, if all outcomes are equally likely, as in the case of a fair die, then the expected value is simply the arithmetic mean, in the long term. If the probabilities are not equal, the expected value takes into account that all outcomes are not equally likely and a weighted average must be used.

Q5.3 What is the expected value for event \(Y\) defined in Q5.1.

5.2.4 Variance

Since we cannot say with certainty what the outcome of an event will be, but only what is likely, or expected, there will be some uncertainty associated with the expected value. Can we commonly expect values to be close to the mean value or far from the mean value?

To quantify the degree to which the values differ from the expected value, or how spread out they may be, we calculate the variance of \(X\), denoted by \(Var(X)\):

\[\begin{equation} Var(X) = \sum_{x=k}^n (x - E(X))^2Pr(X=x) \label{discvarx} \end{equation}\]

Thus, the variance for the outcome of tossing a die is given by:

\[Var(X)= (1-3.5)^2 \times 0.1667 + (2-3.5)^2 \times 0.1667 + (3-3.5)^2 \times 0.1667 + (4-3.5)^2 \times 0.1667\] \[ \; \; + (5-3.5)^2 \times 0.1667 + (6-3.5)^2 \times 0.1667\] \[= 1.04167 + 0.37500 + 0.04167 + 0.04167 + 0.3750 + 1.04167 = 2.917 \]

Again, we can add rows in the PMF table to help with this calculation (Table 5.6).

| \(x\) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| \(x-E(X)\) | -2.5 | -1.5 | -0.5 | 0.5 |

| \((x-E(X))^2\) | 6.25 | 2.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| \((x-E(X))^2\)Pr\((X=x)\) | 1.041667 | 0.375000 | 0.041667 | 0.041667 |

| \(x\) | 5 | 6 | Total |

| \(x-E(X)\) | 1.5 | 2.5 | |

| \((x-E(X))^2\) | 2.25 | 6.25 | |

| \((x-E(X))^2\)Pr\((X=x)\) | 0.375000 | 1.041667 | 2.917 |

The square root of the variance of \(X\) is equal to the standard deviation of \(X\),

\[\begin{align} sd(X) = \sqrt {Var(X)} \end{align}\]

Therefore, for tossing a six-sided die, the standard deviation will be:

\[sd(X) = \sqrt{Var(X)} = \sqrt{2.917} = 1.708\]

Q5.4 What is the variance and standard deviation value for event \(Y\) defined in Q5.1.

5.3 Special discrete distributions

There are several discrete random variables and associated distributions which are frequently used in statistics; here we describe the Bernoulli, binomial and Poisson distributions.

5.3.1 Bernoulli distribution

A Bernoulli random variable is a discrete random variable which can only have two possible outcomes (e.g. success/failure, yes/no, heads/tails) and these outcomes are represented by 0 and 1. The probability distribution takes the value of 1 with probability \(p\) and the value \(0\) with probability \(q=1-p\).

For example, in a single coin toss (denoted by \(X\)) we could represent a head with a 1 and a tail with 0 (or vice versa). The probability of obtaining a head, \(Pr(X=1) = 0.5\) and so the probability of obtaining a tail is \(Pr(X=0) = 1 - 0.5=0.5\). The PMF is shown in Table 5.7.

| \(x\) | 1 | 0 |

|---|---|---|

| \(Pr(X=x)\) | \(p\) = 0.5 | \(1-p\) = 0.5 |

Q5.5 Using the information in Table 5.7, calculate the expected value of a fair coin?

Q5.6 When practising darts, a darts player considers hitting the bullseye (the centre of the dartboard) with a dart as a success and considers missing the bullseye as a failure. The probability they manage to hit a bullseye is 0.25. Create and complete a PMF for the throw of a single dart.

5.3.2 Binomial distribution

Let \(Y_1\), \(Y_2\), …, \(Y_n\) be \(n\) independent, Bernoulli random variables with the same probability of success, \(p\). Independence means that the outcome from one event has no effect on subsequent events. Define a new variable that is the sum:

\[X = \sum_{i=1}^n Y_i\] \(X\) is called a binomial random variable and is described by two parameters, the number of trials \(n\) and the probability of success, \(p\). This is written concisely using the notation \(X \sim \textrm{Binomial}(n, p)\). The random variable \(X\) is the total number of successes out of \(n\) trials and follows a binomial distribution provided that:

- there are only two possible outcomes for each individual trial,

- the probability of success, \(p\), is constant for all trials,

- there are a fixed number of trials, \(n\), and

- each trial is independent of other trials.

For \(x\) in the set {0, 1, …, \(n\)}, the probability mass function of the \(\textrm{Binomial}(n, p)\) distribution will provide the probability of obtaining \(x\) successes out of \(n\) trials:

\[\begin{equation} Pr(X=x) = \frac{n!}{x!(n-x)!}p^x (1-p)^{(n-x)} \label{binompdf} \end{equation}\]

Example Consider a game of darts; assume the probability of hitting the bullseye is 0.25 and that one throw has no effect on subsequent throws (i.e. each throw is independent). What is the probability of hitting the bullseye exactly once in 4 attempts? Let \(X\) denote hitting a bullseye (a success); we have four attempts (or trials) and so \(n=4\), the probability of a success for each attempt is \(p=0.25\). We want the probability of exactly one success, so \(x=1\). Thus, using equation ??:

\[Pr(X=1) = \frac{4!}{1!(4-1)!}(0.25)^1 (1-0.25)^{(4-1)} = \frac{4!}{1!3!} \times 0.25 \times (0.75)^3\]

\[ = 4 \times 0.25 \times 0.421875 = 0.4218\]

We can think of this equation in a more intuitive way and consider each of the components. There are four ways of throwing exactly one bullseye in four attempts - we could hit the bullseye on the first, second, third or fourth attempt. The probability of throwing one bullseye is 0.25 and the probability of missing on three attempts is given by \(0.75 \times 0.75 \times 0.75\). Thus, putting all the components together, we have \(4 \times 0.25 \times (0.75)^3 = 0.4218\) which is what we had previously. It does not matter that the bullseye was the first, second, third or fourth attempt - the binomial distribution does not consider the order of events.

Equation ?? can be used to complete the PMF for this example (i.e. obtain the probability for 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 bullseye in four attempts). However, as we have seen doing these calculations can be a bit long-winded. Fortunately, there is an R function to do this.

5.3.2.1 Doing this in R

To calculate values from a binomial distribution, there are a special group of functions with the suffix, binom. To obtain a probability (i.e. \(Pr(X=x)\)) we use the dbinom function and need to specify the parameters of the binomial distribution (i.e. \(n\) and \(p\)).

# Calculate the probability from a binomial distribution

n <- 4 # number of trials

xsuccess <- 1 # required number of successes

p <- 0.25 # probability of a success

dbinom(x=xsuccess, size=n, prob=p)[1] 0.421875The dbinom function can be used to calculate the probabilities associated with all possible outcomes and thus create the PMF. The possible outcomes range from no bullseyes in four throws up to four bullseyes.

# Create the PMF

results <- data.frame(x=0:4) # Specify all possible outcomes

# Check dataframe has been created correctly

results x

1 0

2 1

3 2

4 3

5 4# Calculate the probabilty of each outcome

results$PMF <- dbinom(x=results$x, size=n, prob=p)

results x PMF

1 0 0.31640625

2 1 0.42187500

3 2 0.21093750

4 3 0.04687500

5 4 0.00390625Another function, pbinom, calculates the CDF as follows:

# Calculate the CDF

results$CDF <- pbinom(q=results$x, size=n, prob=p)

results x PMF CDF

1 0 0.31640625 0.3164063

2 1 0.42187500 0.7382812

3 2 0.21093750 0.9492188

4 3 0.04687500 0.9960938

5 4 0.00390625 1.00000005.3.2.2 Visualising the binomial distribution for different values of \(n\) and \(p\)

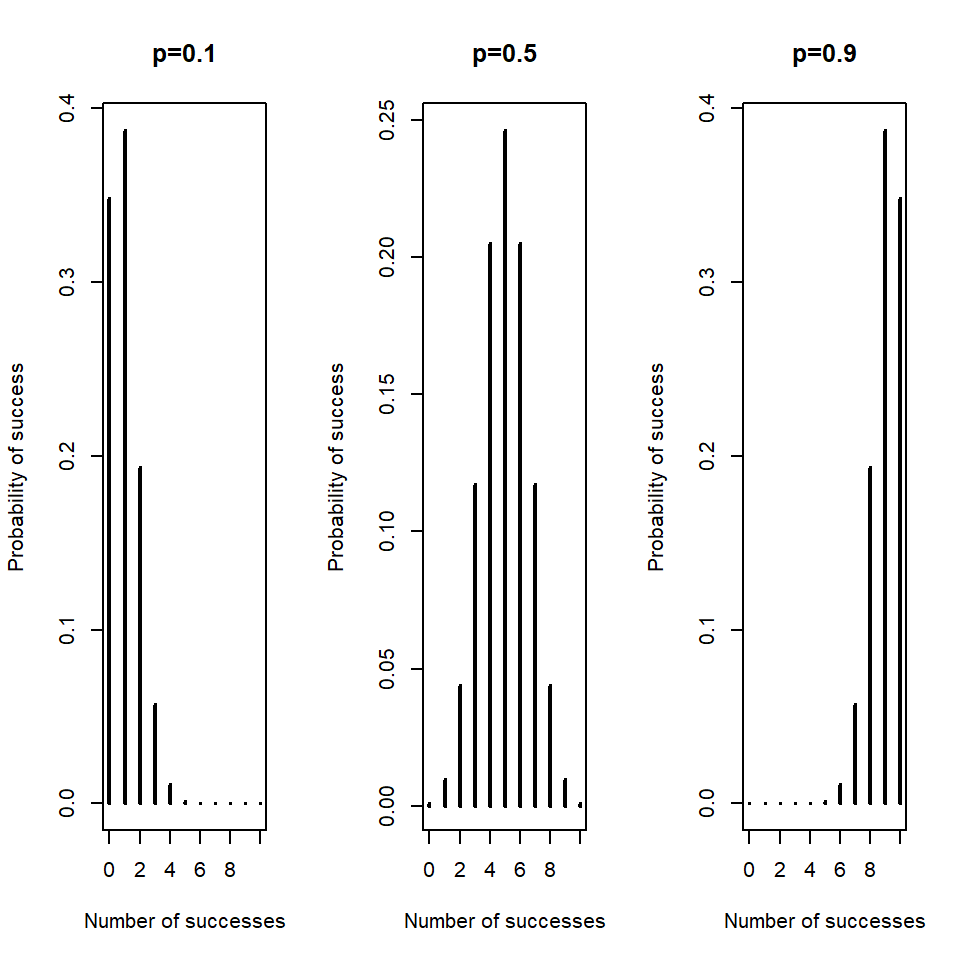

We can think about the change in the shape of the binomial distribution as the probability of success changes, for example, Figure 5.1 shows the PMF for \(n\)=10 and three different values of \(p\):

when \(p\) is low (e.g. \(p=0.1\)) we only expect to see a small number of successes out of the 10 trials and the distribution is skewed to the right - we can’t have fewer than zero successes and we don’t see many high values.

when \(p\) is 0.5 we may expect to see about half of the 10 trials are successful and the distribution is symmetrical - about half the time we see more than 5 successes and about half the time we see fewer than 5 successes (out of the 10 trials).

when \(p\) is high (e.g. \(p=0.9\)), we expect a large number of successes out of the 10 trials and the distribution is skewed to the left - we can’t have more than ten successes and we don’t see many low values.

Figure 5.1: Probability mass functions for three different probabilities, \(p\), and 10 trials.

You can explore some other combinations of \(p\) and \(n\) in Figure 5.2. There is also a live version here

Figure 5.2: Visualising the Binomial distribution. You can see a live version by clicking here

5.3.2.3 Expectation and variance

Using equation ??, we can calculate the probability the darts player throws none, one, two, three or four bullseyes but what is the number of bullseyes that the darts player might expect to hit in the long term, given they have four attempts? For a binomial random variable, there is a simple formula to calculate the expected number.

The expected value of a binomial random variable is given by

\[\begin{align} E(X) = np \end{align}\]

and the variance is found from

\[\begin{align} Var(X) = np(1-p) \end{align}\]

Thus, the number of times the darts player would expect to hit the bullseye with 4 throws is

\[E(X) = 4 \times 0.25 = 1\]

and the variance is

\[Var(X) = 4 \times 0.25 \times (1-0.25) = 0.75\]

Q5.7 In an online quiz, there are 10 multiple-choice questions and 4 possible options for each question, with only one correct option per question. A student, who is short on time, decides to randomly select an option for each question.

a. What is the probability of selecting the correct option for a question?

b. What is the expected number of questions that the student will answer correctly?

c. What is the probability of answering all questions correctly?

d. What is the probability of answering no questions correctly?

e. Is the student more likely to select the correct answer for every question or the wrong answer for every question?

Q5.8 Use the PMF values shown in section 5.3.2.1 for throwing four darts (i.e. the output from R) and equation ?? to confirm that the expected number of bullseye the player could be expected to throw is 1. Use equation ?? to confirm that the variance is 0.75 and hence calculate the standard deviation.

5.3.3 Poisson distribution

The Poisson distribution is used to describe the number of events occurring in some time interval, if these events occur at a known constant mean rate (\(\lambda\)) and independently of the time since the last event. An example of a Poisson variable might be the number of cars passing a certain point within a ten minute period. The interval could also apply to a specified area or volume, for example, the number of trees in a hectare.

A Poisson random variable \(X\) is a discrete random variable with an infinite, but countable, set of possible values, in particular \(X\) can equal values 0, 1, 2, 3, …, and \(\lambda > 0\). This can be written as \(X \sim \textrm{Poisson}(\lambda)\).

The PMF for a Poisson random variable \(X\) is given by

\[ Pr(X=x) = \frac{e^{-\lambda}\lambda^x}{x!}\] For example, the probability that \(X=3\) given that events occur with a mean rate \(\lambda=4\) is found from:

\[ Pr(X=3) = \frac{e^{-4} \times 4 \times 3}{3!} = \frac{1.1722}{6} = 0.1954\]

The underlying process that gives rise to a Poisson distribution is one where:

- \(x\) is the number of times that an event occurs in some interval and \(x\) can take values 0, 1, 2, …

- events are independent, i.e. the occurrence of one event does not affect the occurrence of a second event

- the mean rate of occurrence, \(\lambda\), is independent of occurrences. This is usually assumed to be constant but in reality may vary over time.

- two events cannot occur at exactly the same instant, instead at each very small sub-interval either exactly one event occurs or does not occur.

Example The number of volcanic eruptions, \(X\), in Japan in a year has a Poisson distribution with \(\lambda = 2.4\). What is the probability that there are no eruptions in a given year?

\[ Pr(X=0) = \frac{e^{-2.4} \times 2.4^ 0}{0!} = \frac{0.0907}{1} = 0.0.907\]

5.3.3.1 Doing this in R

Similar to the binomial distribution, there are a suite of functions that can be used to obtain values from a Poisson distribution - the suffix is pois.

Using the example above, the probability of selecting 5 people with XP given \(\lambda=4\) can be found using:

dpois(x=0, lambda=2.4)[1] 0.09071795The CDF is found using the ppois function. For example this function can be used to calculate the probability of selecting less than 3 people with XP (i.e. \(Pr(X \le 3)\)).

# CDF

ppois(q=2, lambda=2.4)[1] 0.5697087# This is equivalent to

dpois(x=0, lambda=2.4) + dpois(x=1, lambda=2.4) + dpois(x=2, lambda=2.4)[1] 0.56970875.3.3.2 Expected value and variance

A Poisson random variable has the interesting property such that the expected value and the variance are equal to the mean rate of occurrence:

\[E(X) = Var(X) = \lambda\] Thus, returning to the example of the genetic disorder, the expected number of people out of one million people with XP is 4 and the variance is 4.

The standard deviation is given by

\[sd(X) = \sqrt{\lambda}\]

Q5.9 The number of people buying an umbrella per day from a shop in April is Poisson distributed with mean rate 4.5. What is the probability that at least 3 people buy an umbrella on an April day? Confirm your calculation using R.

5.3.4 Comparison of binomial and Poisson distributions

The binomial and Poisson distributions are similar, in that they both measure the number of events. However, the binomial is based on discrete events - it provides the probability of a certain number of events out of a fixed number of trials and the probability of success in each trial is the same. The Poisson distribution provides the probability of a certain number of events occurring in a continuous domain, such that there are very many trials each with only one event. It turns out, that if \(n\) is large (i.e. \(n \rightarrow \infty\)) and \(p\) is small (\(p \rightarrow 0\)), the binomial distribution is very like the Poisson distribution.

Example (XP) is a genetic disorder which means that affected individuals are extremely sensitive to ultraviolet rays. The frequency in the US and Europe is approximately 1 person in 250,000 people. If 1,000,000 people are randomly sampled, what is the probability that five people with XP are selected?

In this example, there are a fixed number of trials (i.e. 1,000,000) and so the probability is calculated with a binomial PMF, where the probability of success is 1 in 250,000. To make calculations easy, we do this in R.

dbinom(x=5, size=1000000, prob=1/250000)[1] 0.1562938In this example, \(n\) is very large and \(p\) is small and so we could think of this in terms of the Poisson distribution. The mean rate of XP occurrence in one million people, \(\lambda\), is 4 people per million and we want the probability of selecting 5 people with XP from a million. Hence,

\[Pr(X=5) = \frac{e^{-4}4^5}{5!} = \frac{18.755}{120} = 0.156\]

This is the same result as before, hence, the Poisson distribution is used to model occurrences of events that could happen a large number of times but rarely does (e.g. the occurrence of rare illnesses in a population). Note that these distributions are only similar when \(n\) is very large and \(p\) is small and these days modern computing power makes it easy to do the calculation using the binomial distribution.

5.4 Summary

A discrete random variable is a quantity that can take a finite number of outcomes, but the outcome can not be predicted with certainty, only probabilistically. The probability mass function (PMF) describes these probabilities denoted by \(Pr(X=x)\) and the cumulative distribution function (CDF) provides \(Pr(X \le x)\). Using the PMF table, the expected value and standard deviation can easily be calculated. For specific discrete distributions, these values can be found from simple formulae.

5.4.1 Learning outcomes

In this chapter, you have learnt definitions for

a discrete random variable

probability mass function and cumulative distribution function

and the expected value and variance of a discrete random variable

and been introduced to special cases of discrete random variables such as Bernoulli, binomial and Poisson random variables.

5.5 Answers

Q5.1 First of all, we need to consider the possible outcomes and how many ways there are to obtain them. For two dice (let’s call them A and B), the table below shows all possible outcomes of event \(Y\):

There are 36 possible combinations and the possible outcomes are 2 to 12, inclusive. There is only one way to obtain 2, (i.e. throw a 1 on both A and B) but two ways to obtain a 3 (i.e. 1 on A and 2 on B and vice versa). Using this, we can start to construct the PMF. The probability of obtaining a 2 is \(Pr(Y=2) = \frac{1}{36} = 0.02778\) - a similar calculation is used to fill-in the rest of the PMF table.

Q5.2 a. The CDF follows easily from the PMF in Q5.1 because it is simply the cumulative sum of the PMF.

| y | n | Pr(Y=y) | Pr(Y<=y) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 0.02778 | 0.02778 |

| 3 | 2 | 0.05556 | 0.08333 |

| 4 | 3 | 0.08333 | 0.1667 |

| 5 | 4 | 0.1111 | 0.2778 |

| 6 | 5 | 0.1389 | 0.4167 |

| 7 | 6 | 0.1667 | 0.5833 |

| 8 | 5 | 0.1389 | 0.7222 |

| 9 | 4 | 0.1111 | 0.8333 |

| 10 | 3 | 0.08333 | 0.9167 |

| 11 | 2 | 0.05556 | 0.9722 |

| 12 | 1 | 0.02778 | 1 |

Q5.2 b. The probability that \(Y\) is less than, or equal to, 7 is obtained from the CDF:

\[Pr(Y \le 7) = 0.5833 \]

Q5.2 c. The probability that \(Y\) will be odd is given by:

\[Pr(Y \textrm{ is odd}) = Pr(X=3) + Pr(X=5) + Pr(X=7) + Pr(X=9) + Pr(X=11) \] \[ = 0.0555 + 0.1111 + 0.1667 + 0.1111 + 0.0555 = 0.5 \]

Q5.3 The expected value of \(Y\) is given by:

\[E(Y) = \sum_{y=2}^{12} yPr(Y=y)\] Adding an extra column in the table showing \(yPr(Y=y)\) can help with this calculation:

| y | Pr(Y=y) | y.Pr(Y=y) |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.02778 | 0.05556 |

| 3 | 0.05556 | 0.1667 |

| 4 | 0.08333 | 0.3333 |

| 5 | 0.1111 | 0.5556 |

| 6 | 0.1389 | 0.8333 |

| 7 | 0.1667 | 1.167 |

| 8 | 0.1389 | 1.111 |

| 9 | 0.1111 | 1 |

| 10 | 0.08333 | 0.8333 |

| 11 | 0.05556 | 0.6111 |

| 12 | 0.02778 | 0.3333 |

| Sum | 1 | 7 |

Thus, \(E(Y)=7\).

Q5.4 The variance is calculated from

\[Var(Y) = \sum_{y=2}^{12} (y-E(Y))^2Pr(Y=y)\] Again adding columns in the PMF table can ease this calculation:

| y | Pr(Y=y) | y-E(Y) | (y-E(Y))^2 | (y-E(Y))^2.Pr(Y=y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.02778 | -5 | 25 | 0.6944 |

| 3 | 0.05556 | -4 | 16 | 0.8889 |

| 4 | 0.08333 | -3 | 9 | 0.75 |

| 5 | 0.1111 | -2 | 4 | 0.4444 |

| 6 | 0.1389 | -1 | 1 | 0.1389 |

| 7 | 0.1667 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 0.1389 | 1 | 1 | 0.1389 |

| 9 | 0.1111 | 2 | 4 | 0.4444 |

| 10 | 0.08333 | 3 | 9 | 0.75 |

| 11 | 0.05556 | 4 | 16 | 0.8889 |

| 12 | 0.02778 | 5 | 25 | 0.6944 |

| Sum | 1 | 5.833 |

Thus, \(Var(Y)=5.83\).

Q5.5 Tossing a fair coin will have two outcomes, head or tail. Thus, it is an example of a Bernoulli random variable. Here we assign head=1 and tail=0. The PMF is shown below:

The expected value can be found from equation ?? i.e.

\[E(X) = \sum_{x=k} ^ n xPr(X=x)\] Thus, \(E(X)=0.5\) as shown below:

\[E(X) = \sum_{x=0} ^ 1 xPr(X=x) = 0 \times Pr(X=0) + 1 \times Pr(X=1)\]

\[E(X) = 0 \times 0.5 + 1 \times 0.5 = 0.5\]

Q5.6 There are two outcomes, success (bullseye) and failure (missing a bullseye). The PMF is shown below.

Q5.7 a. The probability of selecting the correct multiple choice option is \[Pr(success)= \frac{1}{4} = 0.25\]

Q5.7 b. In this case, there are two outcomes per question: correct (success) or incorrect and there are a fixed number of questions (trials). Therefore, we consider the number of successes (\(X\)) to follow a binomial distribution, \(X \sim \textrm{Binomial}(10, 0.25)\). The expected number of successes is given by

\[E(X) = np = 10 \times 0.25 = 2.5\]

Q5.7 c. Equation ?? can be used to calculate the probability of \(x\) successes out of \(n\) trials - in this example, we want the probability that all questions are answered correctly - so 10 successes:

\[Pr(X=10) = \frac{10!}{10!(10-10)!}(0.25)^{10} (1-0.25)^{(10-10)}\] \[ = \frac{10!}{10!0!}(0.25)^10 (0.75)^{0} = 0.25^{10} = 0.0953 \times 10^{-5}\]

Q5.7 d. Similarly, if the student answers no questions correctly, then \(x=0\):

\[Pr(X=10) = \frac{10!}{0!(10-0)!}(0.25)^0 (1-0.25)^{(10-0)}\] \[= \frac{10!}{0!10!}(0.25)^0 (0.75)^{10} = 0.75^{10} = 0.0563\]

Q5.7 e. The probability of \(Pr(X=0)\) is much greater than the \(Pr(X=10)\), hence the student is more likely to choose the wrong option for all questions than choose all the correct options. This is commonsense perhaps, because there are more wrong options to choose from.

Q5.8 Let \(X\) be a throw of four darts, we use the PMF table to obtain the \(E(X)\).

| x | Pr(X=x) | xPr(X=x) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.31640625 | 0 |

| 1 | 0.421875 | 0.421875 |

| 2 | 0.2109375 | 0.421875 |

| 3 | 0.046875 | 0.140625 |

| 4 | 0.00390625 | 0.015625 |

| Total | 1 | 1 |

Thus, by summing the final column in the table, we see that the \(E(X)=1\).

The variance and intermediate calculations are given in the table below.

| x | Pr(X=x) | (x-E(X))^2 | (x-E(X))^2.Pr(X=x) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.31640625 | 1 | 0.31640625 |

| 1 | 0.421875 | 1.23259516440783e-32 | 5.20001084984554e-33 |

| 2 | 0.2109375 | 1 | 0.2109375 |

| 3 | 0.046875 | 4 | 0.1875 |

| 4 | 0.00390625 | 9 | 0.03515625 |

| Total | 1 | 0.75 |

Thus, \(Var(X)=0.75\) and so \(sd(X)=\sqrt{0.75}=0.866\).

Q5.9 Here, we want \(Pr(X \le 3)\) and \(\lambda=4.5\), thus,

\[Pr(X\le 3) = Pr(X=0) + Pr(X=1) + Pr(X=2) + Pr(X=3) \] \[ = \frac{e^{-4.5}4.5^0}{0!} + \frac{e^{-4.5}4.5^1}{1!} + \frac{e^{-4.5}4.5^2}{2!} + \frac{e^{-4.5}4.5^3}{3!}\]

\[ = 0.0111 + 0.04999 + \frac{0.2249}{2} + \frac{1.0123}{6} = 0.3423\]

We can confirm this calculation in R using the function ppois:

ppois(q=3, lambda=4.5)[1] 0.342296# Check this calculation

dpois(x=0, lambda=4.5) + dpois(x=1, lambda=4.5) +

dpois(x=2, lambda=4.5) + dpois(x=3, lambda=4.5)[1] 0.342296